| Class Time Required |

Activity 1A: 2 class periods |

| Materials Needed |

|

| Teacher Preparation |

Investigate school area for outdoor sites, prepare student field materials, gather materials for backpacks, find and assemble materials and create classroom centers Read Teacher Background for more information. |

| Prior Student Knowledge | Prior experience with use of science tools and/or with hunting and gathering would be helpful, though not necessary. |

| Vocabulary |

aquatic, awareness, boundaries, compare, data, describe details, environment, eye level, ground level, marine biologist, notice, observation, plot, role-play, science notebook, sort, subsistence, weigh, wonder. Specific names of plants and animals around the school environment. |

| Science GLEs Addressed |

K-12 Standards A1, A2, C2, G2, G3, G4 |

Overview: Students begin to notice and discover aquatic plants and animals in this introductory investigation. They take a walk to get an overall view of the plants and animals around them, and begin to observe, wonder, and ask questions. Next, they practice looking closely as they examine and discover what is happening in one small square of the schoolyard. After learning about the roles of marine biologists and subsistence users, and finding out about tools that can help them make observations, students continue to explore and discover aquatic life through a variety of learning centers set up in their classroom.

Overview: Students begin to notice and discover aquatic plants and animals in this introductory investigation. They take a walk to get an overall view of the plants and animals around them, and begin to observe, wonder, and ask questions. Next, they practice looking closely as they examine and discover what is happening in one small square of the schoolyard. After learning about the roles of marine biologists and subsistence users, and finding out about tools that can help them make observations, students continue to explore and discover aquatic life through a variety of learning centers set up in their classroom.

Focus Questions:

- What plants and animals live in the environment around our school?

- What's happening in one small square, near or in the water?

- How do scientists and subsistence users discover aquatic plants and animals?

Activity 1A: Around Our School

(2 class periods)

Focus Question: What plants and animals live in the environment around our school?

Engagement (5-10 minutes):

Explain to the students that they will be taking a walk around the playground, or in another area adjacent to the school. Brainstorm with the children about what they can expect to see. Make a list of plants and animals that they might see during the school year. Ask students to think about what they might see in a different season of the year, and why some plants and animals are seen during certain times of the year.

Exploration (20-30 minutes):

Practice observation skills on a walk outside the school: look, listen, and notice the surrounding environment. Assist children to “see” the plants and animals that live near the school. Encourage them to look down at the ground around them, at eye level (trees, bushes) and also up higher (tall trees, mountains, sky). It’s important that children get the big picture of their local environment before being asked to look into a smaller area in the next activity. Encourage them to name what they see, and point out birds, trees, and other things that they notice. Have children gather in small groups to explain their view through simple games such as “I Spy,” a sound game (listening), and a camera game. For the camera game, have children gaze around and then focus on one thing, and then use their ear as the button to take the picture with their eye (camera).

Explanation (30 minutes):

Back in the classroom, help children discuss what they saw. Gather in the group area and write their ideas on a list. The list will be used to support children’s thinking when they write in their science notebooks, and it will be useful to divide the list in some way. You might divide the list by “level” (ground level, eye level, sky level) or by “area” (near a creek, next to the road, by the building).

Have children write in their science notebooks, using the left side of a clean page. If appropriate, divide the page into three boxes with horizontal lines to match the class list.

Ask students to think about their time outside and record three things that they noticed on the walk. Use any “levels” or “areas” from the class list, and have them choose one thing from each; for example, they might choose one thing from the ground or near their feet, one thing from eye level, and one thing taller than them. They should list details that they noticed about each thing. As students finish writing, have them share with each other, and again with the whole group once they are gathered together.

Elaboration (20 - 30 minutes, next day or later):

Remind students of the walk they took to look for signs of animals and living plants. Show them an O-W-L chart and explain that making lists of what they have observed will help to keep their “scientist’s eyes” open to new plants and animals they learn about.

Ask the students to take a moment to remember what was most interesting. If time has passed, guide children through the walk once again, in their mind’s eyes. Describe the route taken and have children describe what they noticed. Write responses on the chart under “O”: “What we have observed.”

If there are photos of the initial walk, children can review what plants and animals were observed. They can also refer to their science notebooks. Use the initial list to remind students of what they saw and how they described it. Continue adding to the Observation list until everyone’s ideas are recorded.

Move on to the “W,” asking students what they have wondered about as they walked and noticed plants and animals. Record all ideas and questions, and support and guide children to wonder about what they have seen, heard, felt, and noticed. Encourage every student to have at least one question they are wondering about. Many of the questions may be similar, and the children with similar questions could work together to start talking about their ideas. How will we find out that information? Where could we go to ask?

In a new science notebook entry, have children draw a picture and write about their wonderings.

Evaluation

Listen to the students’ ideas and wonderings to begin to get an idea of misconceptions and/or questions that can be used for inquiry lessons during the unit.

This initial activity can be used as a pre-assessment. Use the attitude checklist to note beginning attitudes of science learning and outdoor awareness. Also, note which students are engaged, using senses and vocabulary, and which students will need more support for focused attention and ways to participate. As another optional pre-assessment, you may wish to use an initial science notebook entry to document beginning awareness of local environment, before the unit begins.

Labels, details, and standard data (date, weather, temperature) should be a part of each science notebook entry.

Activity 1B: One Small Square

(1-2 class periods)

Focus Question: What’s happening in one small square near or in the water?

Engagement (10-25 minutes):  Introduce the book One Small Square Backyard and notice the border on the cover (See alernative titles in the Materials section that may match your local environment better.) Choose a few pages of the book that best match your local “backyard” to read aloud. Ask the students what they notice inside the border on the cover. Tell students they will be exploring “one small square” of their school yard. Show them a meter of survey tape and a magnifying glass, and model the use of each. Make a square with the survey tape, and tell students this square of space is called a “plot.” You might use classroom materials (legos, beads, pattern blocks) in the square and describe aloud as you look and wonder! Tell students they will have to look very closely in their plot to discover all the things living--both plants and animals.

Introduce the book One Small Square Backyard and notice the border on the cover (See alernative titles in the Materials section that may match your local environment better.) Choose a few pages of the book that best match your local “backyard” to read aloud. Ask the students what they notice inside the border on the cover. Tell students they will be exploring “one small square” of their school yard. Show them a meter of survey tape and a magnifying glass, and model the use of each. Make a square with the survey tape, and tell students this square of space is called a “plot.” You might use classroom materials (legos, beads, pattern blocks) in the square and describe aloud as you look and wonder! Tell students they will have to look very closely in their plot to discover all the things living--both plants and animals.

If needed, have students practice in the classroom using the survey ribbon and defining the “space.” For practice, discuss the details of what is within their spaces, using ordinary classroom items. The goal is to go from looking at the bigger picture of the environment to zeroing in on one small square and to realize that there are many plants and probably animals within that small space.

Exploration (20 minutes):

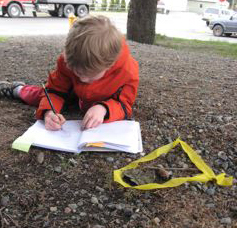

Give each student a meter of survey tape, a magnifying glass, toothpick flags, and their science notebook. As a class, walk to an appropriate place that you have selected and have students look for a space they want to explore. Describe boundaries so that you can keep the group of children within eyesight. When each student has found their plot, they define the “one small square” with the survey ribbon. Then they study the plot closely for signs of life and other unique features, marking five things that they find most interesting with toothpick flags. Tell students to place the toothpicks carefully so they do not accidently “pin” or “spear” living plants and animals. After students have examined their one small square of earth and used their five flags, encourage them to record three or more of their discoveries in their science notebook.

Explanation (20 minutes):

Have your science explorers invite one another to their one small square to view their discoveries and unique features. You may want to have student pairs set up ahead of time for sharing. As children are exploring and sharing, take a tour of each student’s one small square and ask questions to encourage thinking. Document each small square with a camera if feasible.

Back in the classroom, encourage students to pair up and share three or more things they discovered in their one small square. What is similar in both squares? What is different? How are they related?

Elaboration (10-15 Minutes):

As homework, have students take home a one-meter length of survey tape to do the same assignment in their own backyard. Ask them to bring back documentation of what they found. Post their drawings and writings in the classroom and use them to talk about similarities and differences in backyard environments.

Evaluation:

Observe and identify students’ abilities to “see” findings in the one small square and to use their science notebooks to explain what they saw. You may also ask students to reflect on their findings in their notebooks or out loud.

Activity 1C: Biologist and Subsistence Backpacks

(2 class periods plus exploration time at learning centers)

Focus Question: How do scientists and subsistence users discover aquatic plants and animals?

Engagement (20-30 minutes):

Introduce an “outdoor scientist” and a “subsistence food gatherer” one at a time, on the same day or at different times. Dress up in a coat, hat, raingear, rubber boots, and a backpack that contains the appropriate tools. Introduce the contents of a backpack to the children, one item at a time, and have children share their thinking about what each item is for.

Marine Biologist Backpack: Magnifying glass or hand lens, notebook, clipboard/Rite in the Rain paper, pencil, camera, tide book, identification field guide, field guide book (marine or freshwater), measuring tape or ruler, warm clothes, thermometer, maps, aerial photo, sampling jars, first-aid kit, flashlight, water bottle, snack, cell phone or VHF radio).

Introduce the class to the jobs of a biologist or a marine biologist, discussing questions such as “What is a biologist?” “What do they do?” “What about a marine biologist?” “What do they do?”

Seas and Rivers Subsistence and Personal Use Backpack: Tide book, flashlight, pail, gloves, hat, raincoat, piece of net, knife (pretend), fishing pole, berry-picker, map, identification chart, water bottle, snack, cell phone or VHF radio. Discuss subsistence with the students, asking questions such as, “What if we couldn’t buy food at the store?” “Who gets food from the land, sea, or river?” “What are some traditional uses of land, sea, and river plants and animals?” “How have the Alaska Native people taught us about edible plants and animals?” Explain that when a person gets some of their food or craft materials (plants or animals) from land or water, it is called subsistence or personal use.

Exploration (1-2 hours, multiple days):

Create a dramatic play center in an area of the classroom to simulate a beach or riverbank. You might cover the area with butcher paper and paint a simple backdrop of your local outdoor area. Add a few local props--rocks, shells, stuffed river/marine animals, paper-stuffed fish, plants (dried grass or beach grass, etc) along with books, posters, charts, and other resources. Put the Biologist and Subsistence Backpacks in this area.

Give students the opportunity to explore and play with the backpacks in the center, in small groups during Choice or Discovery time.

Later, introduce a Biologist’s Lab and Subsistence Camp center with more specific activities that allow children to use tools and learn about roles.

Explanation:

Notice how the students are using the science tools and guide their understanding with follow-up lessons in the use of magnifying glasses or thermometers. Students can begin to understand how they will use these tools at the beach later.

Having a “debrief” session a few times during the use of the backpacks will encourage deeper understanding and thinking about how they are used. This can be done with the whole group or with smaller groups as the backpacks are being used.

Elaboration (20 minutes):

Compare the role of a biologist and an Alaska Native subsistence user through discussion and use of photos and/or books depicting people in those roles. How are they the same? What tools do they use that are the same? How are they different? How do we learn from each other? What do they learn from each other?

Scientists share their information when they write books and reports. Alaska Natives share their information through stories, legends, learning from their family, and books.

In what other ways are marine plants and animals used?

Evaluation:

Assess children’s understanding of the roles of biologists and subsistence users, and their appropriate use of tools, through ongoing observation.

Activity 1D: Alaska Seas and Watersheds Discovery Centers

Focus Question: What do you notice about ____________?

(The open-ended questions are important for child-guided explorations.)

Engagement:

Take time to notice a particularly interesting shell or rock. Draw children’s attention to it with either an “I Spy” approach or twenty questions with the object in a brown paper bag.

Afterward, introduce Seas and Rivers Discovery Centers one at a time. Encourage children to use the centers appropriately--“explore like a scientist”--“tell other scientists in the room what you find!”

Centers may include:

- A sand table with shells.

- A water table with shells and plastic marine animals and plankton nets.

- A magnet board with pictures of aquatic or marine animals.

- A flannel board with silhouettes of marine animals.

- A pan balance scale with shells/rocks for weighing and comparing.

- Alaska Seas and Watersheds Bingo Game.

- Freshwater Bingo Boards and Cards.

- Marine Bingo Boards and Cards.

- Marine Biologist’s Lab (activity 1C).

- Subsistence Camp (activity 1C).

Keep a tub of books, puzzles, science tools, and commercial games in the classroom where it will be accessible to all of the center users.

Exploration:

Allow children to self-select the center they want to explore, with ample time to explore and discover at their own pace. Center time should be 1 to 1½ hours in duration.

Explanation:

Debrief with students after center time. What did they notice? What kinds of animals are on the bingo game? How can you describe them? How did you use a science tool? How were you a scientist today as you used the tools and discovered.

Elaboration:

Students will learn from each other when they share their ideas. They will get ideas for rediscovery and replay during the next day’s center time. Move and change centers as children lose interest. Centers can continue throughout the Alaska Seas and Watersheds unit of study, to support understanding and child-directed learning.

Evaluation:

Science notebooks can be used with varying choice of focus--looking at a shell, noticing the characteristics of a sea creature (plastic representation), comparison of sand or rocks. Observation and anecdotal notes are another form of assessment that guides student learning. A checklist can also be used for assessment.

Teacher Preparation:

|

Tips from Teachers |

|

If you do not have plant and animal life nearby for students to observe, you might consider one or more of the following to allow for close observation: - Create a mini-biosphere in your classroom.- Provide books with close-up photos of the beach or water and ask students to make note of what they see. - Show a video or movie with footage of a beach, pond or underwater environment. - Consider a walk to a nearby area if your playground does not have any signs of life. |

Explore the area around your school to find a route for the walk and a place for the “one small square” activity. An area with plants and animals (even grass and worms or insects) will make the activity much more interesting than a plot of playground that has few signs of life.

- Prepare science notebooks for student use, and make a blank O-W-L Chart.

- Measure tape and gather the other materials needed, and assemble student kits. Prepare additional tape and instructions for homework.

- Gather materials and assemble backpacks.

- Prepare Backpack centers.

- Collect materials and prepare classroom centers.

- Read Teacher Background for more information.

Curricular Connections:

To connect this investigation to art and social studies, students can draw a map of the school area, adding names of things that they saw on their initial walk, and using photos or drawings to document what they saw.

Math learning can be connected to the “one small square” by having students investigate beginning concepts of area, and estimating “How much is everyone’s small square altogether?”

Literacy is reinforced through the writing and drawing activities in the investigation, and children can learn about drama through role-playing activities.

| Student Handouts |

Science notebooks |

| Items for Group Display |

O-W-L Chart: Large piece of chart paper labeled with columns Book: One Small Square Backyard by Donald M. Silver and Patricia Wynne, McGraw Hill, 1997. Alternatives (depending on local enviroment): One Small Square Seashore, One Small Square Arctic Tundra. |

| Material Items |

|

| Facility/Equipment Requirements |

Outdoor area near school |

Alaska Science Grade Level Expectations Addressed:

In Investigation 1, First Grade students begin to build toward these K-12 Alaska Science Standards:

Science as Inquiry and Process

(A1) develop an understanding of the processes of science used to investigate problems, design and conduct repeatable scientific investigations, and defend scientific arguments.

(A2) develop an understanding that the processes of science require integrity, logical reasoning, skepticism, openness, communication, and peer review.

Concepts of Life Science

(C2) develop an understanding of the structure, function, behavior, development, life cycles, and diversity of living organisms.

History and Nature of Science

(G2) develop an understanding that the advancement of scientific knowledge embraces innovation and requires empirical evidence, repeatable investigations, logical arguments, and critical review in striving for the best possible explanations of the natural world.

(G3) develop an understanding that scientific knowledge is ongoing and subject to change as new evidence becomes available through experimental and/or observational confirmation(s).

(G4) develop an understanding that advancements in science depend on curiosity, creativity, imagination, and a broad knowledge base.

Essential Question:

Enduring Understandings:

Ocean Literacy Principles Addressed:

|

Overview: In this 8-11 day investigation, children begin to identify features of specific plants and animals, and to sort them into groups. They describe properties of shells or other objects, and use those characteristics to sort them in various ways. They focus on specific animals and practice observing and describing their characteristics, and are introduced to groups of invertebrates that are sorted according to their features. To review and reinforce what they have learned, the students play a

Overview: In this 8-11 day investigation, children begin to identify features of specific plants and animals, and to sort them into groups. They describe properties of shells or other objects, and use those characteristics to sort them in various ways. They focus on specific animals and practice observing and describing their characteristics, and are introduced to groups of invertebrates that are sorted according to their features. To review and reinforce what they have learned, the students play a  knowledge of invertebrate species.

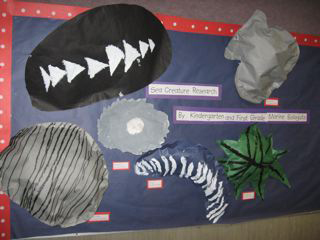

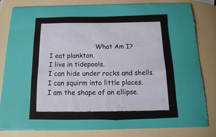

knowledge of invertebrate species.  Overview: In this 9-12 day investigation, children begin by continuing to learn about the wide variety of aquatic plants and animals in their region. Each child then chooses a special plant or animal to research, depict, and share with the class. They go on to learn more about their special species and others as they explore life cycles and tide-related behaviors, and end the investigation by making and sharing plant and animal riddles.

Overview: In this 9-12 day investigation, children begin by continuing to learn about the wide variety of aquatic plants and animals in their region. Each child then chooses a special plant or animal to research, depict, and share with the class. They go on to learn more about their special species and others as they explore life cycles and tide-related behaviors, and end the investigation by making and sharing plant and animal riddles.

Overview: This 3-day investigation includes a 1-3 hour field trip. Students make predictions about where they will find plants and animals, and go to a field site to explore and test their predictions. After having time to explore, students conduct a detailed investigation of “one small square” at the field site. Back in the classroom, they share their findings and then make a detailed representation of their research “square” using drawings, notes, and labels.

Overview: This 3-day investigation includes a 1-3 hour field trip. Students make predictions about where they will find plants and animals, and go to a field site to explore and test their predictions. After having time to explore, students conduct a detailed investigation of “one small square” at the field site. Back in the classroom, they share their findings and then make a detailed representation of their research “square” using drawings, notes, and labels. Overview: In this investigation, children will reflect on what they have learned as they complete the O-W-L chart that they began in Investigation 1. They will plan ways to share their new knowledge with the whole school and/or community and prepare for an Alaska Seas and Watersheds Celebration. After learning and practicing ways to present information, they will display and present their work to others. The investigation extends over 3 or 4 class periods, and culminates with a long afternoon or evening celebration.

Overview: In this investigation, children will reflect on what they have learned as they complete the O-W-L chart that they began in Investigation 1. They will plan ways to share their new knowledge with the whole school and/or community and prepare for an Alaska Seas and Watersheds Celebration. After learning and practicing ways to present information, they will display and present their work to others. The investigation extends over 3 or 4 class periods, and culminates with a long afternoon or evening celebration.