Investigation 5 - Sharing What We Know

| Class Time Required |

2 class periods plus 1-2 hours to participate in celebration |

| Materials Needed |

|

| Teacher Preparation |

Organize all of the student work and materials from the unit. Set dates and invite others to Celebration. Set up room to facilitate presentations. |

| Prior Student Knowledge |

Experiences that students have had during their K year with art, writing, reading and presentation will assist their ability to be successful throughout this unit. |

| Vocabulary |

Communication, presentation, all vocabulary used during the unit |

| Science GLEs Addressed |

A1, A2, C2, C3 |

Overview: This investigation allows students an opportunity to share their thinking. They share and communicate their experiences and understanding using their science notebooks, art, photos from the field trip, classroom work, and a mural. First, they practice in the classroom and then share their thinking and work as part of a classroom and/or whole school celebration of the Alaska Seas and Watersheds Curriculum.

Overview: This investigation allows students an opportunity to share their thinking. They share and communicate their experiences and understanding using their science notebooks, art, photos from the field trip, classroom work, and a mural. First, they practice in the classroom and then share their thinking and work as part of a classroom and/or whole school celebration of the Alaska Seas and Watersheds Curriculum.

Focus Questions:

- How do we find out information?

- How can we, as scientists, naturalists, and biologists share our information?

- How do we share our ideas and thinking?

Engagement (10 minutes):

Reread information about living and nonliving things, to model how to present information. Model different ways of sharing information: Use a science notebook, and then use a puzzle or mini-book in another example. Another way to share might be to roleplay a scientist coming together with other scientists to ask for help in identifying newly found habitat (dress in outdoor gear: coat, hat, and rain-pants with magnifier, science notebook, backpack, etc.)

Students will be using their science notebooks to note experiences and information from their work in describing living and nonliving things. They may also choose to use a mini-book, additions to the class mural, or a sea creature puzzle to "teach" about their understanding.

Exploration (30 minutes):

Work with the students to create a rubric that helps them understand how they are expected to share their information (see Evaluation below). Organize the students to give their own presentations and/or explanations of one aspect of their learning, giving them choices of presentation methods that work for the classroom schedule.

Group the students into pairs to practice sharing their findings. Invite them to roleplay during their presentation, asking fellow scientists (peers) to listen to their findings. Students listen to each other as they share presentations of living and nonliving things. Encourage students to listen carefully and then provide feedback to the practice presenter, asking questions and/or making connections to living and nonliving things based on their own experiences during the classroom unit study.

Science notebooks and all other work should be ready and available when students pair-share with each other. The room should reflect student learning and their experiences during the entire unit.

Explanation (40 minutes):

Students ask each other questions, which can be about specific living and nonliving things presented or about possible connections to different characteristics discovered during the unit. The pair-share practice is about 5-10 minutes long with students asking each other questions at the end.

This is an important part of the learning process. When students ask each other questions, the students giving the information will be encouraged to defend their thinking, share their ideas, and/or agree and disagree with each other about living and nonliving things. This is the place where students get to use their evidence to clarify understanding. They can share specific information found through books and/or experiences. Characteristics (colors, shapes, and sizes) and specific ways living things move will be a key part of the information presented.

Gather the class together to debrief as a whole group. Help students brainstorm what makes a good audience for other students to present their information. Have a few students demonstrate their explanations and allow questioning. Use your rubric to discuss the presentations and talk about what makes a good presentation. Help students to connect their explanations to habitat information, book learning, and their field experience as well as visits from guests and explorations in the classroom.

Elaboration (1-2 hours):

Take part in a Whole School Celebration of the Alaska Seas and Watersheds Curriculum, or organize an opportunity for students to share their learning with others.

One way to organize the overall communication part of the unit is to set up a "scientific conference" for the culmination of the unit. Students can display information, artwork, books, and exhibits from their lessons. Invite parents, community members, and/or other classes to come, view, and listen. All through the unit the teacher should call each discussion and/or investigation of information a “mini-conference” letting children know that their final information will be shared at the scientific conference. In this way, children will be expected to offer a piece of science information for the conference, emphasizing that everyone’s thinking would be important to the whole process.

Gather students together for the scientific conference. Students will act as groups of “scientists” who will report their findings to the rest of the group. It is fun if the lead educators are quirky conference reporters during this conference, so that key questions can be asked of the scientists: “How did you come about these findings?” and, to a member of the‘audience’: “How would you have gone about answering this question?” In particular, it is key to prod students to ask and answer their own questions about the data they are collecting and the merits of their methodology.

Evaluation:

Create a rubric with the students (see rubric ideas in resources) so that they will understand the different aspects of presenting information to others. Criteria might include speaking in a clear voice, showing evidence, asking for questions, and sharing enthusiasm. It is important for students to be part of the process so they can understand the expectations and purpose of sharing information. Roleplay with the class to assist this process once the rubric is created. Ask students to watch for best ways to give information.

Teacher Preparation:

|

Tips from Teachers |

|

Do presentations informally, in "fair booth" style where parents and staff can mingle and inquire. |

Read the Teacher Background for more information.Find exemplars in science notebooks, mini- books, on the mural, and in other work to demonstrate the sharing process to students. Be sure that student work and materials from the entire unit are accessible to students during this investigation.

Decide on a date and time, then prepare and send out an invitation to parents and possibly flyers to the community to come to your celebration. Students may help to generate the invitations. Organize refreshments and a seating area for demonstrations, explanations, and other activities.

Curricular Connections:

Language Art. The investigation provides experience in speaking and listening.

Art. Students practice presenting and critiquing art.

| Student Handouts |

Science notebooks |

| Items for Group Display |

Any charts, lists, and displays used during the unit |

| Material Items |

|

| Facility/Equipment Requirements |

Hallway, wall, and other display space. Gathering space for student presentations with "audience seating." |

Alaska Science Grade Level Expectations Addressed:

In Investigation 5, kindergarten students begin to build toward these K-12 Alaska Science Standards:

Science as Inquiry and Process

(A1) develop an understanding of the processes of science used to investigate problems, design and conduct repeatable scientific investigations, and defend scientific arguments.

(A2) develop an understanding that the processes of science require integrity, logical reasoning, skepticism, openness, communication, and peer review.

Concepts of Life Science

(C2) develop an understanding of the structure, function, behavior, development, life cycles, and diversity of living organisms.

(C3) develop an understanding that all organisms are linked to each other and their physical environments through the transfer and transformation of matter and energy.

Essential Question:

Enduring Understandings:

|

Overview: Children go outdoors to explore a local habitat. They see, feel, and think about the living and nonliving things in the water. Science notebooks are used to gather information about what they find. Students use their background knowledge from prior classroom experiences, the initial field trip, classroom investigations, and other observations to notice and observe the living and nonliving things in their environment. Students have plenty of time to explore and discover before being asked to write and draw in their science notebooks.

Overview: Children go outdoors to explore a local habitat. They see, feel, and think about the living and nonliving things in the water. Science notebooks are used to gather information about what they find. Students use their background knowledge from prior classroom experiences, the initial field trip, classroom investigations, and other observations to notice and observe the living and nonliving things in their environment. Students have plenty of time to explore and discover before being asked to write and draw in their science notebooks. Gather students together, explain the boundaries, and remind the students of field trip etiquette. Agree on a signal for gathering (such as a whistle) and let students know they will have 30 minutes to explore before they take part in a more focused activity. Be sure that each volunteer has a list of the children in their group and all of the possible tools they will need (nets, pencils, rulers, magnifiers). Students will explore the freshwater or saltwater habitat, using skills of observation, documentation, and connecting the information they have had in the classroom investigations to these outdoor experiences. Allow students to use the first 30 minutes to explore freely and notice animals and/or plants, rocks, sand, mud, etc. (living and nonliving) that are in the area. After 30 minutes, bring students back together with a signal.

Gather students together, explain the boundaries, and remind the students of field trip etiquette. Agree on a signal for gathering (such as a whistle) and let students know they will have 30 minutes to explore before they take part in a more focused activity. Be sure that each volunteer has a list of the children in their group and all of the possible tools they will need (nets, pencils, rulers, magnifiers). Students will explore the freshwater or saltwater habitat, using skills of observation, documentation, and connecting the information they have had in the classroom investigations to these outdoor experiences. Allow students to use the first 30 minutes to explore freely and notice animals and/or plants, rocks, sand, mud, etc. (living and nonliving) that are in the area. After 30 minutes, bring students back together with a signal. Overview: In this 6-9 day investigation, children assemble simple puzzles to learn more about aquatic animals and their life cycles. They look closely at the parts of a small aquatic animal with a listening and drawing activity, then learn to describe and explain the things in aquatic environments by making mini-books, a class book, and a large class mural.

Overview: In this 6-9 day investigation, children assemble simple puzzles to learn more about aquatic animals and their life cycles. They look closely at the parts of a small aquatic animal with a listening and drawing activity, then learn to describe and explain the things in aquatic environments by making mini-books, a class book, and a large class mural. Have children pair up and share the animals that they drew in their science notebooks.

Have children pair up and share the animals that they drew in their science notebooks. books, posters, drawings, science notebooks and other resources around the room to use for getting ideas. These mini-books will focus on shape, size, and color. Children may start their book with illustrations and/or with words. The teacher emphasizes that the pictures must match the words. For example: "I see a red sea star." "I see an oval limpet." "I see a large sea anemone." "I see a dark rock." "I see squishy mud." "I see a white barnacle." "I see a ______." "I see a _____."

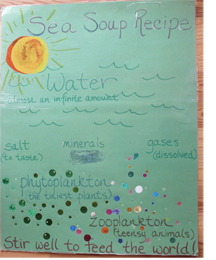

books, posters, drawings, science notebooks and other resources around the room to use for getting ideas. These mini-books will focus on shape, size, and color. Children may start their book with illustrations and/or with words. The teacher emphasizes that the pictures must match the words. For example: "I see a red sea star." "I see an oval limpet." "I see a large sea anemone." "I see a dark rock." "I see squishy mud." "I see a white barnacle." "I see a ______." "I see a _____." Overview: In this 2-3 day investigation, children begin to learn about the tiny plants, animals, and nonliving things that are in sea, river, or pond water. They listen to a read-aloud, explore at learning centers, roleplay, and then make a recipe for Sea Soup.

Overview: In this 2-3 day investigation, children begin to learn about the tiny plants, animals, and nonliving things that are in sea, river, or pond water. They listen to a read-aloud, explore at learning centers, roleplay, and then make a recipe for Sea Soup. understanding of what is in the water around them. To support student success with this independent drawing and labeling activity, you may wish to supply them with cutouts of sea soup ingredients that can be colored or examples to draw from.

understanding of what is in the water around them. To support student success with this independent drawing and labeling activity, you may wish to supply them with cutouts of sea soup ingredients that can be colored or examples to draw from. Overview: In this 4-5 day investigation, students begin their discovery of aquatic environments, and start to notice that water is all around them, in their neighborhoods, backyards, oceans, rivers, ponds, and creeks. They take a first look at "Our Big Blue Planet" with a globe game, inspect jars of water and land to think about the differences, and act as outdoor "Water Detectives" to explore and map water on a walk near their school. They finish up the investigation by taking a closer look to see living things in their jars of water.

Overview: In this 4-5 day investigation, students begin their discovery of aquatic environments, and start to notice that water is all around them, in their neighborhoods, backyards, oceans, rivers, ponds, and creeks. They take a first look at "Our Big Blue Planet" with a globe game, inspect jars of water and land to think about the differences, and act as outdoor "Water Detectives" to explore and map water on a walk near their school. They finish up the investigation by taking a closer look to see living things in their jars of water. Ask the students for their ideas about where water might be found. You might write the ideas on chart paper, on cards, or on a clipboard that can be used on the walk as a checklist to see how many places the students were able to predict.

Ask the students for their ideas about where water might be found. You might write the ideas on chart paper, on cards, or on a clipboard that can be used on the walk as a checklist to see how many places the students were able to predict.